Written by Soleil Parks, TAG Intern Fall 2022

In Gallery 2000, a hanging wall in the back of the Cultivating Community Through Art exhibition supports La Llorona Desperately Seeking Coyolxauhqui, a bright pink screenprint by Alma Lopez. The print was created in 2003 as a part of Sam Coronado’s Serie project. During November 8th’s TAG Tuesday talk, Austin Community College Professors Dr. Lydia CdeBaca-Cruz and Dr. Gary Moreno joined participants to discuss the layered imagery and myths behind the artwork.

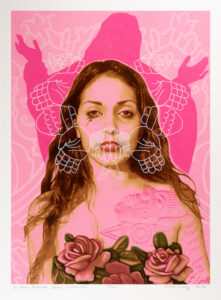

Placed largely in the center of the artwork is a portrait of a young woman. Behind her is a silhouette of La Llorona, a tragic figure in Hispanic lore, with her hands outstretched. In the background, a pattern represents the dress of the Virgen de Guadalupe. Around the young woman’s head, and around the neck of La Llorona, is the necklace of Coyolxauhqui’s mother Coatlicue. Both women are figures from Aztec mythology. The necklace is made of hearts, hands, and a head that almost covers the mouth of the subject. On the woman’s chest is an engraving of Coyolxauhqui, making a layered representation of mothers and daughters.

Alma Lopez, La Llorona Desperately Seeking Coyolxauhqui, 2003, screen print, 28 x 22 in.

In Dr. CdeBaca-Cruz’s talk, she discussed the significance of Coyolxauhqui and Coatlicue’s story. Coyolxauhqui is the daughter of Coatlicue, an Aztec earth and mother goddess. Coatlicue was sweeping (often done as a ceremonial cleansing act) when a feather fell into her apron and impregnated her. She became pregnant with Huitzilopochtli, patron god of the Aztec Mexicas (Nahuatl-speaking indigenous people in the Valley of Mexico). Her daughter and four hundred other sons found her sudden pregnancy to be shameful, so Coyolxauhqui led them on a charge to kill their mother. When Coatlicue talked to her son in the womb and told him they were out to get her, he reassured her. When Coyolxauhqui and her brothers arrive, Huitzilopochtli is born completely grown and armed. He begins slaughtering his brothers one by one until only he and his warrior sister are left. He cuts off all of her limbs, and after he severs her head, he throws it into the sky, creating the moon. Dr. CdeBaca-Cruz, who also lectures at UT Austin, explained that to many people in Mexican and Mexican-American communities, this represents the dismemberment of community, specifically the moment a motherly connection is irreparably split. When Coyolxauhqui’s brother cuts off all her limbs to save their mother, he also sliced through her relationship with the family. From the artist’s point of view, this piece relates to the mothers of missing young women in towns along the Texas and Mexico border and the pain they feel when their daughters are forcibly taken.

This breaking of bonds between mother and child is also seen in the story of La Llorona. Dr. Gary Moreno, who also acts as Director of ACC’s Latin American Center (“El Centro”), told participants the story of an Indigenous woman who married a Spanish man directly after the conquests in Mexico. After he abandoned her, she drowned her two children in grief. La Llorona became overcome with regret and drowned herself, resulting in her becoming a spirit that roamed bodies of water saying “¡Ay, mis hijos!”, or “Oh, my children!” To contextualize this story, Dr. Moreno recounts the experiences of Malinali, also known as Malintzín or La Malinche. Malinali was the daughter of a rich landowner (also known as a cacique). She was the only heir to the land until her father was murdered and her mother remarried. To forcefully disinherit her, her stepfather fakes her death and sells her into slavery. Because of her ability to translate from Spanish to Nahuatl, she was made the translator of conquistador Hernán Cortés. She later had his child, Martín Cortés. Because of this, Malinali is seen as a traitor to Indigenous people and has been portrayed as so for hundreds of years. However, Dr. Moreno invited us to look at it from her point of view. She was an Indigenous woman on her own, eventually with a son who was a part of a new generation of mixed-race Mexicans. Dr. Moreno argues that she was given a difficult start to life, and likely did the best she could for herself and her child. Her son would eventually be taken from her by Hernán, allowing us to connect back to La Llorona. She was also an Indigenous woman with mixed-race children. Similarly to Malinali, she may have been worrying about the societal pressures on herself and her children, but without the leverage of formal education. Another shared theme amongst Mexican lore and mothers in border towns is not just the breaking of bonds, but the longing of a mother when her child is removed from her care.

According to the Serie project, the artwork is representative of the 300 young women and girls who have been murdered and gone missing in Juarez, Mexico (https://serieproject.org/product/alma-lopez-2/). The imagery of Coyolxauhqui and Coatlicue represents the relationships that are broken when a young woman is taken by force. La Llorona represents the mothers that desperately wait for their return.

Recent Comments